Bridging the Racial Divide

This is the first in a three-part series about the Putnam County School District desegregating schools. On Tuesday, the Palatka Daily News will examine more of the effects of desegregation and the major players in Putnam County, including Dr. William Higgins, Judge Percy B. Revels and others. On Wednesday, the impacts and thoughts of Palatka South High School class of 1970 graduates and graduates from Palatka Central High School will be explored.

Unlike many of its neighboring counties, the Putnam County School District integrated schools in the late 1960s with its own plan.

And while there were flare-ups and tensions in bridging a centuries-long racial divide, the district fought local pressure and made sure Black and White students went to school together.

Carey Ferrell, the superintendent who oversaw the hectic time period more than 50 years ago, reflected on the process that fundamentally changed Putnam County.

West and South Putnam County, with far fewer than Palatka’s 7,000 students, had already integrated. Then in the 1969-1970 school year, it was time to start desegregation in Palatka. But Ferrell said the issue was nearly sidetracked at a meeting that had to be scheduled at the Palatka South High School auditorium due to the large crowd.

Ferrell estimated there were more than 1,000 people at the meeting, which lasted more than six hours. Speaker after speaker, Ferrell said, wanted the district to follow St. Johns County’s example and fight the federal government tooth and nail in opposing desegregation.

Ferrell and a U.S. Office of Civil Rights employee answered questions and argued the district changing on its own was better than years of federal oversight.

No one was leaving the meeting in the early morning hours and Ferrell said some of the board members were wavering on the district’s promise.

“People were demanding an answer that night to go back on desegregation,” Ferrell said. “It was midnight or a little after midnight. It got pretty hot. One of the board members slumped in his chair. He was unconscious and an ambulance was called. The other board members escaped making a decision right then.”

The four remaining members felt they could not make a decision without the other member’s consent, Ferrell said, and the board did not break its promise at future meetings.

The push to integrate started in 1954 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, where the court unanimously ruled separating White and Black students in schools violated the 14th Amendment. However, the 14-page decision did not outline how to integrate. Ferrell notes the decision only called for districts to integrate “with all deliberate speed.”

The incentive came in 1963 with the Civil Rights Act, proposed by President John F. Kennedy, which aimed to end discrimination based on race, religion or nationality and in most public places, including schools. After Kennedy was assassinated, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed the legislation forward and the law was signed in 1964.

Ferrell joined the district in 1961, working on the superintendent’s staff. He became superintendent in 1966 and held the position until 1971, when he took a position with the state Department of Education.

According to Ferrell, district leaders did not want to cede control to the federal government. He said the district had money saved from issuing bonds in 1963 that could have been used for desegregation costs.

The first step to desegregation was the west and south ends of the county, which had fewer schools and students than the Palatka area. There was a White school in Melrose serving grades one through 12, a Black elementary school in Johnson and a White elementary school in Interlachen.

Ferrell said the Melrose school was transitioned to elementary only, and with bond funds, the district built a junior-senior high school in Interlachen. The district improved the capacity of Interlachen Elementary to accommodate Black students, he said.

In Crescent City, two schools served grades one through 12 for White and Black students.

The Black school was Middleton High on the west side of Crescent City, and the White high school, Crescent City High School, was on the east side. Ferrell said he told city and community leaders due to attendance zones mandated by the federal government, some White students would be zoned to go to Middleton and be in the minority.

That information, he said, persuaded them to build a new junior-senior high school and transitioned Crescent City High School to an elementary. Middleton High was closed.

The new Interlachen and Crescent City junior-senior high schools opened for the 1968-1969 school year.

Palatka would be tougher to desegregate. Fearing federal and societal repercussions, Circuit Judge Percy B. Revels issued a court order to establish an interracial committee and an injunction prohibiting activities that would disrupt the committee’s work. These pivotal moves organized the process and kept the community informed.

“Revels probably had more foresight than any public official in the county before the Civil Rights Act was passed. He was talking about it and thought it would be passed,” Ferrell said. “He saw the potential things that could happen.”

A key member of the committee, Dr. William Higgins, was one of the few Black dentists in Palatka and he conversed about race issues with Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Shuttlesworth. Higgins’s son, Sean Higgins, said a cross was burned in his yard and another area nearby in 1968.

“My father fired a shotgun one time in the air, and they scattered,” Sean Higgins said.

The process and beginning of integration

The Office of Civil Rights in Washington D.C. was in constant contact with the district, Ferrell said. The 1965-1966 school year was one of the “freedom of choice” years where parents essentially could transfer their children to schools within their attendance zones rather than students being assigned to schools by race.

Ferrell was the district director of business affairs at the time and oversaw sending transfer requests to parents. He said most requests at the elementary school level, about 110 requests of mostly Black students, were approved. That figure was fewer than 4% of Black students, Ferrell recalled.

Ferrell was appointed as the superintendent the next year and led faculty integration in the 1966-1967 school year. He said none of the Black teachers selected to teach in White schools refused. The success of the faculty integration, other than one instance in Interlachen Ferrell refers to later in this story, led to more transfers.

Ferrell said it was clear the small amount of student transfers was not enough to fully integrate the district. The 1968 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Greene v. New Kent County School, ruled the “freedom of choice” was ineffective and told lower courts methods such as zoning were more effective.

A major problem for Ferrell and his staff was the blowback from sending White students to Black schools. The district had proposed using bond funds to build a combined school in Palatka in 1965, but the offer was met with refusals from community leaders. The bond funds, which helped desegregate South and West Putnam schools, were no longer available.

Ferrell’s concerns were the dilapidated Central Academy Elementary and Central Academy High School, built in 1925. Ferrell said the conditions at Central Academy Elementary, which was located on Washington Street near railroad tracks, were so bad teachers and students sometimes had to wade through water to get on campus and pause instruction when the train came by.

He said James A. Long Elementary School was relatively new and the district didn’t receive complaints from White parents about sending students to the school.

The Office of Civil Rights told the district it could hold off on desegregation to issue a bond via an election to build a new elementary and high school in Palatka for a combined $5.4 million. Ferrell said the school board, helmed by board member George C. Miller, committed to the Office of Civil Rights that desegregation would begin based on zoning if the bond election failed.

The bond election on May 13, 1969 failed. Ferrell’s opinion on the bond referendum’s failure lies in two ideas: general opposition to desegregation from residents and portions of South and West Putnam who did not want to pay higher taxes for what was essentially a Palatka issue.

Tensions and flare-ups

Desegregation was an unpopular sentiment for many, and despite the best efforts of the district, Ferrell said there was intimidation and property damage, though the outcome was far less than violence in other counties and cities.

One of the few West Putnam instances Ferrell recalled was the intimidation of a Black teacher named Mary Strickland at the newly integrated Interlachen Elementary School in 1966.

Strickland previously taught at Oak Grove Elementary School in Johnson and was regarded as one of the best teachers in the area, according to Ferrell.

He said a man from New Jersey, who claimed to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan, led a campaign to remove students from the school because of Strickland’s presence. This would have hurt the district’s funding for the school. After some convincing from Revels, Putnam County Sheriff’s Office deputies escorted buses.

Ferrell met with the man and others from the group in Interlachen on the condition they were not wearing hoods, though he said he was never able to confirm if the group was officially a part of the Klan. Ferrell said when he told the group about the desegregation plans, they were unaware the new high school would have integrated students and faculty.

Ferrell said the anti-integration group’s efforts included having a student of Strickland’s accuse her teacher of attacking her. Strickland was arrested and the district posted bond and had the school board attorney provide her defense. In a non-jury trial, the judge ruled in favor of the teacher.

Strickland kept teaching the student, and the parent told Strickland she had been pressured by the group to make the allegation, Ferrell said.

In Palatka, a meeting of Central Academy High School parents angered about how desegregation would impact the band led to the slashing of Ferrell’s tires in September 1969. Students would be moved from much-loved band director Abe Alexander to what they believed was an inferior band at Palatka South. Ferrell said an out-of-town man with a bottle of liquor egged on a rowdy crowd of about 200 parents and others.

Ferrell said he attempted to keep a lid on the night’s events to not stir up any racial trouble.

“Frankly, they had a better band than the White high school did,” Ferrell said. “We had trouble convincing the parents (that) the students needed to go over (to Palatka South High School).”

Ferrell recalled how Alexander slipped him through a back door of the community center when there was a short break. Ferrell saw his car was damaged and he had to wait for a tow late into the night. The incident inspired him to install a cumbersome car phone in his trunk, he said with a laugh.

Two other problems Ferrell remembered was damage to buses at Palatka South High School with “vulgar and derogatory statements” painted on them, and a break-in and fire at James A. Long Elementary School before the school was desegregated in 1969. Though the motive and arsonist were not identified.

Final steps and reorganization

After the school board’s decision in 1969, the district had three months to come up with a desegregation plan for Palatka. The district decided on a plan covering all of Palatka rather than a phased plan.

The initial guidelines of the plan called for each school to be 70% White and 30% Black for students and faculty. The district made school-walking zones and busing for students with the same 70% White and 30% Black ratio.

Parents were mailed where their students would be attending and their right to a hearing. A day-long meeting was scheduled to hear appeals and most were turned down, Ferrell said.

To develop attendance zones, the district, using an IBM keypunch records system, made files for each student that documented age, school, grade level and race. The district then drew maps and ran the student cards through a sorter and was able to reach the 70%-30% ratio.

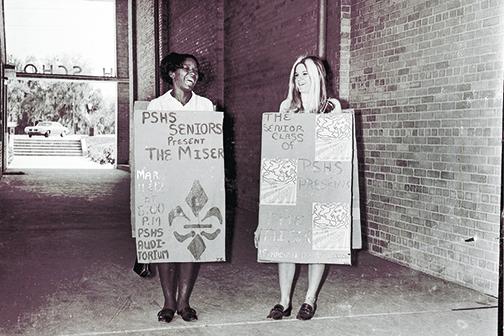

Palatka Senior High School was renamed to Palatka South High School, and Central Academy High School was renamed Palatka Central High School for the 1969-1970 school year. Palatka Central High School was closed in 1977 as the district merged the schools into what is now Palatka High School.

The exception was Central Academy Elementary School. To maintain the already-fragile relationship between White parents and desegregation plans, Ferrell said it was not in the district’s best interest to immediately send White students to the elementary school. The Office of Civil Rights allowed the district to keep the school 100% Black until the school could be closed and students transferred.

Because ninth grade used to be considered a middle-school grade, the district, Ferrell and his staff split the ninth-grade class of Palatka Junior High School between Palatka South and Palatka Central.

Transfers of sixth-graders from elementary to middle schools throughout the county left space in the elementary schools to accommodate Central Academy Elementary students.

Though schools were effectively desegregated, Central Academy Elementary was the last step, which was overseen by Ferrell’s successor, former Palatka South Principal John Gaines.

Desegregation’s effects

Ferrell left the Department of Education in the mid-1980s. He spent about 12 years between assistant superintendent roles in Orange and Seminole counties before retiring. Ferrell, 90, now lives in Sanford. He said those two districts, and Putnam’s neighboring county, St. Johns County, had to comply with stricter federal guidelines more than 40 years later because they fought the desegregation in the beginning.

Facing an election in 1968, Ferrell said he was startled by the two candidates running against him. Neither candidate’s focus was desegregation. He said that is when he knew despite public opposition, desegregation was inevitable.

“The issue of segregation never came (up in the election). That’s when I realized the public had gotten over it,” Ferrell said. “(Another) superintendent would have been in a position to reverse the work we had done. I consider it the last real big hurdle.”

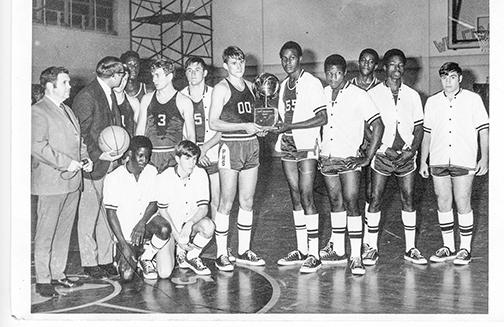

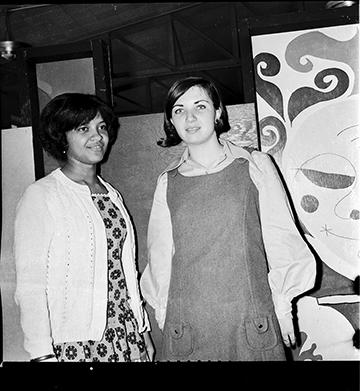

With desegregation, children got to know each other, and those friendships spilled into the community, Ferrell said.

A 2011 National Bureau of Economic Research study found for Black adults born between 1950-1975, and attended desegregated schools, earnings rose 5%. The graduation rate for a Black student rose 1.3%-2.9% for each year in a desegregated school.

In addition, there were major health effects for students who attended desegregated schools, the study found.

“Desegregation also resulted in significant long-run improvements in Blacks’ adult health, as measured by self-assessed general health status. The effect of a five-year exposure to school desegregation is equivalent to being seven years younger.”

After years of division, the Putnam County School District took the first step for its community in an issue that engulfed the country. It was only a start, Ferrell said, but Black students got a glimpse of what a desegregated society looked like.

“(Desegregating schools) was effectively a movement to desegregate the community,” Ferrell said. “Putnam schools had to take the lead in doing that. We all learned a lot in the process.”

Coming Tuesday: The major players in the move to desegregate schools.