This is the first part of a series that highlights local women, many of whom were migrant workers, who grew up in San Mateo and became teachers.

Three women will be recognized in this segment and the stories of another three San Mateo women will be shared in the next segment.

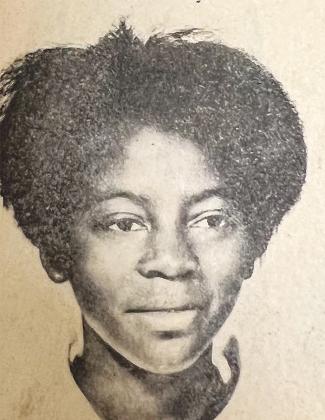

Retired educator Regina Gilyard-Thomas said she decided to seek a higher education when her son was 10 days old.

She grew up in San Mateo, picking oranges after school and spending summers migrating up the East Coast to harvest vegetables with her family.

“That was summer vacation,” Gilyard-Thomas said.

She graduated from Palatka South High School in 1970. By 1977, she had enrolled in what was then Santa Fe Community College in Gainesville, she said, where her new journey began.

Growing up, Gilyard-Thomas said, she liked school. She attended Central Academy for the first part of her high school years, where she played the clarinet in the school band and was ranked high in her class when it came to grades.

However, things changed for Gilyard-Thomas when schools integrated during her senior year and she had to attend Palatka South. Because she wanted to graduate from Central Academy, she didn’t become involved in any activities at her new high school and lost her class ranking.

“My senior year was probably one of my worst years,” she said.

Some of her friends at Central Academy got sent to different schools as integration in the 1969-1970 school year mandated Black and White students attend the same schools.

Before then, Central Academy had been the only all-Black high school in Putnam County. Voluntary integration began slowly before Gilyard-Thomas’ final year of high school, and some Black students chose to go to integrated schools but didn’t pick that same path.

“We skipped school because we didn’t want to be there and we’d meet some of our friends from … Palatka Central (High School),” Gilyard-Thomas recalled.

She said she remembers being treated differently by other people in the Black community as well because she and her family were migrant workers.

“We were second-class citizens,” she said. “You weren’t expected to achieve because of your status.”

Gilyard-Thomas, a retired teacher, credits her aunt, Lilla Holsey, for inspiring her to become an educator because Holsey received her teaching degree and was a professor at East Carolina University during the time Gilyard-Thomas went to college. Gilyard-Thomas also said her younger sister, Sandra Gilyard, the current Putnam County School Board chairwoman, was always in her corner and helped her get further her education.

Gilyard-Thomas said she received her associate degree from Santa Fe, received a bachelor’s degree in education from the University of North Florida and obtained a master’s and specialist degree from Nova Southeastern University.

“It felt like I had accomplished the world,” she said. “My kids were there. They were happy. They were excited (and saying), you know, ‘My mom’s going to be a teacher.’”

Gilyard-Thomas said she started teaching at Kelley Smith Elementary School in Palatka and then moved to Melrose Elementary School.

She also taught in Orlando and Miami but moved back to Putnam County in 2003 to work for the Putnam County School District on an administration level. She eventually retired from the district in 2015.

“Being a migrant, growing up in that environment, has made me … a stronger person,” she said.

Gilyard-Thomas said she tells people she went “from the poor house to the White House” because she spoke at the White House Conference on Families under President Jimmy Carter’s administration. She spoke from the perspective of migrant families.

She said, “It was a journey, one that I appreciate and I respect more and more every day.”